Compulsive Gambling 911

By Marjorie Preston

“One to 2 percent.

Statistically speaking, the numbers seem negligible. But for anyone who meets the diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder (an estimated 2 million to 4 million people, or up to 2 percent of U.S. adults), the condition can be destructive, life-altering and even life-threatening, increasing the risk for self-harm including suicide.

Symptoms include an irresistible urge to gamble, with increasingly high stakes; restlessness or irritability when attempting to cut back or stop; using gambling to cope with guilt, anxiety or depression; and chasing losses.

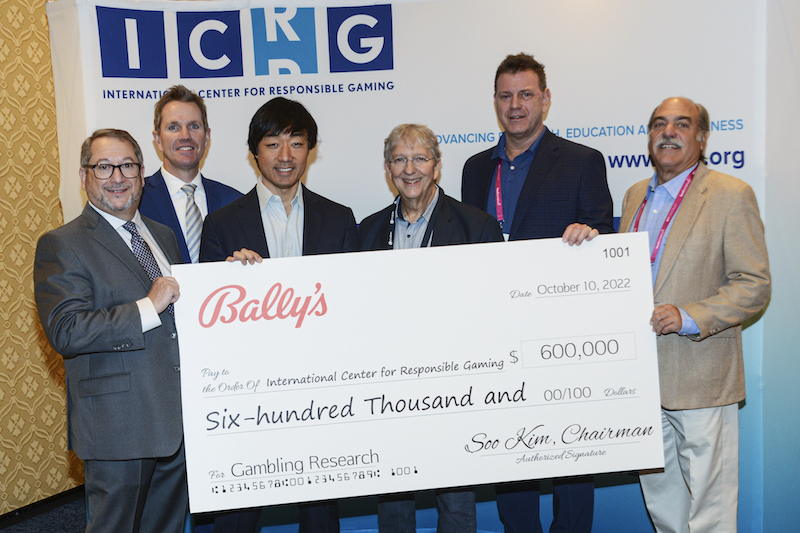

A number of agencies are working to unravel the mysteries of the baffling disorder. There’s the usual alphabet soup of acronyms, including the International Center for Responsible Gaming (ICRG) and the National Council on Problem Gambling (NCPG), as well as state-based organizations and support groups like Gamblers Anonymous.

But the biggest player of all—the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—is sitting this one out.

Ten years ago, gambling disorder became the first behavioral (non-substance) addiction in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Yet the U.S. government (which this year earmarked $43 billion for the prevention and treatment of drug abuse) “hasn’t allocated one penny” for problem gambling, says Felicia Grondin, executive director of the nonprofit Council on Compulsive Gambling of New Jersey (CCGNJ).

That’s left states and casino operators to pick up the tab. The New Jersey council, which offers public education, professional training and referrals for problem gamblers, is funded by the state through casinos and online gaming licensees.

While the money is essential and welcome, it’s not close to enough, says Grondin. “In 2021, New Jersey ranked No. 3 in the country for gross gaming revenue, but dropped to No. 19 of the 42 states that allocate funds to problem gambling, treatment and prevention.”

That year, New Jersey’s per-capita investment was “34 cents a person.” Despite limited resources, says Grondin, “we just have to keep on hammering our message and getting it out there.”

The Only Game in Town

The industry’s role in funding interventions sometimes meets with skepticism, with critics suggesting that casino-funded research must be biased. ICRG board members include representatives of Caesars Entertainment, Wynn Resorts and the Las Vegas Sands Corp. NCPG contributors include Caesars, Las Vegas Sands, the NFL, FanDuel and Mohegan Gaming.

But James P. Whelan defends the integrity of the research. The director of the Tennessee Institute for Gambling Education and Research (TIGER), which receives ICRG funding, says industry donors “have a voice in saying what questions are important from their perspective, but they don’t drive the research agenda.”

Without ICRG funds, he adds, “we wouldn’t be able to ask the questions we’re asking. It’s not NIH money by any stretch, but there’s no other vehicle for doing it, because the federal government is silent here.”

Christine Reilly, the ICRG’s secretary, treasurer and senior research director, says independent peer reviewers and the organization’s Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) evaluate all proposals, with the latter making the final decisions on grant funding.

“Neither the governing board nor the donors have any say or influence about what ICRG supports,” Reilly says. “This structure makes it possible for us to focus solely on merit when reviewing and selecting grant projects.”

Recently, Ted Hartwell was named executive director of the Nevada Council on Problem Gambling. A recovering gambling addict, Hartwell acknowledges that most research done in the field is funded by the IGRC, with an assist from the industry.

“There’s a pretty good firewall between the origin and the dollars, and the science has been fantastic for the most part,” Hartwell says. “The reason we know gambling is an addictive disorder is because of the contributions of the industry to that process.”

Over the years, the ICRG (which originated as a national body in 1996) has invested more than $31 million in research and public programs, such as educational materials for parents and teachers, an online intervention for college gamblers, and a screening test that can be used by health professionals and individuals to determine if a gambling problem exists.

The Washington, D.C.-based NCPG is looking to shape national policy on the subject. Founded in 1972, the nonprofit—which is neither for nor against legal gambling—also provides education to federal, state, tribal and international governments and agencies.

The NCPG is also behind the 1-800-GAMBLER network, which became the national helpline number in June 2022, and the annual National Conference on Problem Gambling.

Growing Problem, Growing Awareness, or Both?

In a 2021 survey, the NCPG asked 2,000 adults about their gambling habits. The survey showed that, from 2018 to 2021, an additional 26 million people were betting online, and there were also 15.3 million more sports bettors (that growth occurred as legal sports betting got off the ground and iGaming increased, and also included the pandemic years of 2020-21).

New Jersey saw an astonishing 870 percent increase in online and sports betting revenue between 2018 and 2022, which Grondin attributes in part to advertising. In 2020, operators spent $292 million on TV ads alone. A year later, that figure had soared to $725 million.

“You see gambling ads every single day,” especially for sports betting and online betting, Grondin says. “We’re bombarded on billboards, radio and television. And the more revenue that’s generated, the more calls we get.”

That could indicate a spike in problem gambling. But it could also mean greater awareness that’s leading more gamblers to seek help. “Traditionally, the introduction of new options to gamble results in a temporary increase that abates over time,” says Whelan. When it comes to sports betting and iGaming, “I don’t think the sky is falling, but we need a national study to really evaluate.”

Reilly adds, “Every new form of technology—for example, automobiles, television—raises concerns about risks to public health, and online gambling is no exception. But we need evidence to prove one way or another about the potential harms.”

Along with more legal betting options and operators’ hard sell, the sheer accessibility of gambling is cause for concern. “We’ve gone from a culture where used to have to take a trip to gamble to making a drive to gamble to now just reaching for the phone,” says Whelan.

“If you’re on a sports wagering app, they’re going to offer you bets throughout a competition—parlays within a game, live bets throughout the game, prop bets. And we know that heavy advertising impacts those who are already having problems.”

As Hartwell notes, an increase in helpline calls “doesn’t automatically translate to more people in trouble. They’re now just finding out, ‘Oh, there’s help for this thing I’m experiencing.’

“The good thing is that those advertisements now usually come with 800-GAMBLER prominently featured. Having a national helpline number is huge—it’s immediately recognizable and memorable.”

Time for Washington to Intervene?

The lack of hard data about gambling disorder could be hampering national action on the issue; so could that “1 percent” statistic (some sources believe the percentage of afflicted gamblers is higher).

“Besides, if it’s 1 percent of the population, we’re still talking about millions of people,” says Whelan. “Are harms increasing? I don’t know. No one’s going to know unless we’re able to study it, and the lack of federal dollars doesn’t allow us to ask this question with great integrity.

“The current appetite at the federal level is to leave things to the states. Also, the NIH doesn’t have a natural mechanism for funding this research. It has institutes that were created for problems like drugs and alcohol, but not for addictions in general. So gambling and other non-substance use addictions don’t really have a home or a voice at that level.”

That may be in the pipeline. According to the NCPG website, the proposed Gambling Addiction Recovery, Investment and Treatment Act (GRIT) would set aside half of the federal sports excise tax revenue for gambling addiction treatment and research. Of that, 75 percent would be distributed to the states for gambling addiction prevention and treatment through the existing Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant program.

Cole Wogoman, the NCPG’s government relations manager, says the legislation will be introduced by Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal, “likely by the end of the year but perhaps in January.”

“Oh, it definitely needs to happen,” says Whelan. “Our ability to ask the big important questions, gaining precision and knowledge about what treatments work for whom, requires the level of funding that only the federal government can provide.”

In the late 1990s, Nevada researchers developed what they called “Science-based Framework for Responsible Gambling: The Reno Model.” The paper, published in the Journal of Gambling Studies in 2004, emphasized personal responsibility as a cornerstone of responsible gaming, adding that consumers must be informed of the risks.

According to the ICRG website, the authors called on “health providers, scientists, the gaming industry, elected officials, regulators, community organizers and consumers, to unite and address gambling-related issues.” Even so, the Reno Model clashed with later thinking that emphasized “gambling operator duty of care and consumer protection.”

‘The Three-Legged Stool’

Hartwell believes it’s a shared responsibility. “We need to put more of the onus both on industry and government to provide that framework, so people know what they’re dealing with. Then we can expect them to take more personal responsibility. It does need to be all three legs of the stool.”

He also believes it’s possible to “pull people back into healthier behavior before they develop an addictive disorder,” thereby creating a sustainable player base.

“I’m a prime example of someone for whom (gambling disorder) was chronic and progressive over time. But I don’t know that would have been the case if we’d caught it earlier or if I’d been more aware of some of the warning signs. Long-term player sustainability starts with not marketing directly to people who have or could have problems.”

He supports using player data used for marketing to send responsible-gaming messages: “‘Hey, Mr. Johnson, thanks for being a loyal customer. Over the past five years, your average spend with us has been this level, and in the past three months it’s been up here. We just wanted to reach out, make sure everything’s OK.’

“There’s some evidence that proactive, individualized messages can pull people back into more sustainable behavior. Maybe (operators can) reward people who use RG tools, offering them an incentive for doing that.”

If existing organizations come into a windfall from Washington, they could do a deeper dive into the causes of gambling disorder, develop better solutions, enhance current programs and add new ones. Grondin wants to see public service announcements, “Like, ‘This is your brain on drugs.’ There’s nothing like that right now.

“We also support advertising restrictions,” like those developed in the U.K. and European Union. “We’re working on warning-label language indicating that gambling is risky, can become addictive and can lead to catastrophic life consequences. But there has to be more funding.”

Hartwell wants to build more youth awareness. “This is where the behavior starts. Ultimately responsible gambling awareness should start in education, identifying people who may be transitioning into a gambling problem to proactively message to pull them back into healthier behavior before it becomes a true disorder. There’s some research that suggests it can be done. It’s just a matter of having the political will and the fiscal resources to pull off those types of studies.”

He calls the GRIT Act “a no-brainer. It allocates monies that are already being collected by the federal government, but have never gone to anything related to gambling.”

Whelan also supports federal intervention as well as ongoing support from the gaming industry. “The industry and government regulators need to understand their social responsibilities when it comes to people who experience gambling harms.

“They don’t like me when I say this, but they don’t want to be the tobacco industry.” Meanwhile, he adds, “I think they’re doing the right thing.”